The Toaster Paradox

For the past few months, I have been engaged in the (stupidly) ambitious project of reading Sigfried Giedion's 1948 tome Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonymous History. Much like my last self-assigned homework reading, The Prodigious Builders, the author's non-native English and the age of the book makes for some unconventional prose. Gideon traces the history of manufacturing from the earliest rumblings of the Industrial Revolution on through World War II, covering every conceivable process along the way. For instance, he goes into not only mechanized reaping, but grain milling and bread-baking and packaging and preservatives and so on. The detail is exhaustive, well-illustrated with patent drawings.

Giedion was born in 1888, and his lifetime spanned many of the great leaps in manufacturing technology that have made modern life possible. He was able to document many of those changes in real time, writing and lecturing extensively on the growth of modern design, the Bauhaus, and architects of the International Style. Since his death, in 1968, technology has continued its relentless march forward, but many of the processes he chronicled in Mechanization Takes Command have remained archaic. Minerals still must be wrenched from the earth and refined into something useful with great heat and pressure. Today, we've replaced some of that brutal labor with machines, or even robots, but the basic story is unchanging.

The book; thickets of bookmarks intact.

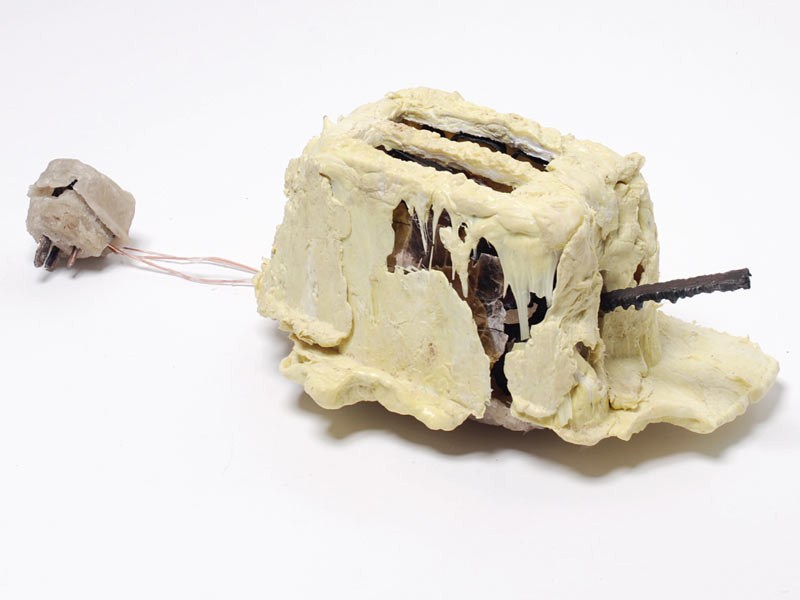

One of my favorite blogs, Root Simple, recently put up a post about repairing a toaster -- one of the simplest household machines. As it turns out, they are vastly more complicated than their task would indicate. Root Simple linked out to a TED Talk by designer Thomas Thwaites, who tackled this very contradiction in his Toaster Project. He set out to build a toaster from scratch, refining metal ores; building a nickel heating element; and melting down post-consumer plastic and shaping it in a mold hacked from a tree trunk. The resultant object, a sort of globular ur-toaster that looked as if it had dragged itself from the primordial ocean of industrial design, worked for about "5 seconds" before shorting out.

Root Simple's repair attempts were unsuccessful -- the break in the heating element that had to be soldered was inaccessible and made of hair-thin wire. Thwaite's efforts were similarly thwarted, hampered by the improvisatory engineering necessary to smelt ore in one's backyard. This general incomprehensibility -- in a toaster, of all things -- doesn't even begin to approach the truly baffling and unrepairable objects in our lives, like smartphones. A key tenet of today's technological advances is that they (supposedly) make things more accessible, but the tools that wrench that access from the world are they themselves, well, inaccessible.

Mr Thwaite's ur-toaster, via TED.

Sigfried Giedion lived through the invention of the first toaster, in 1893; the first pop-up toaster, in 1919; and the high-speed dough mixer and automatic bread-slicer, both in 1928. He took the mechanization and standardization of bread, in particular, as evidence of " . . . the period [after 1900] when anonymous corporations penetrate nearly every province of living."(p. 196) Though Giedion never (curiously) mentions the invention of the toaster, he goes to great lengths to link the standardization of crops, growing seasons, threshing technology, milling, mixing, nutritional science, and consumer taste to the end product: a cubic, spongy white loaf with soft crust. Whole-wheat loaves, home baked into irregular boules, don't it in the neat, rectangular slots of a standardized toaster. So, for a mechanized toaster to even become possible, thousands of other advances had to march forward in lockstep to produce a uniform food product that was adapted to the machine.

I consider myself a fairly self-reliant person -- not too knowledgable about cars, maybe, but I can fix my bike, build a chair, or add a deck onto your house. Most DIY-ers and makers today would make the same claim. But take away one or two key items, like a Philips-head screw or a bottle of wood glue, and that handiness evaporates. This is the Toaster Paradox: Giedion's dark prediction about "anonymous corporations" has progressed so far that none of my furniture designs are even possible without an impossibly long and tangled tail of standardized parts that I cannot make myself.

This gets to the heart of the maker impulse. After all, none of us are really rendering something from whole cloth -- we are merely rearranging bits of mechanical magic provided for us by corporations. Doing it yourself is not really self-reliance; in fact, it is even more consumer-dependent because one must purchase dozens of pieces instead of one pre-assembled object from a single manufacturer.

So why do we make? Because it renders our corner of the world comprehensible again, building the knowledge to replicate, repair, and respect the objects we live with. It is a more human relationship with the things that make the world inhabitable. It is, to paraphrase Giedion, our contribution to anonymous history.