DIY TV

As a kid, I was often up first on Saturday mornings. I tended to wake up early naturally, a trait that has served me well later in life (though I don't bounce up quite as clear-eyed as I used to . . .) Being up first had a lot of advantages in a household of six -- free of supervision or sibling interference, I could put sugar on my cereal, and I could get in front of the TV without being bothered. We didn't have cable growing up, and I never much cared for cartoons, so I tuned to PBS and got my DIY on.

Dean Johnson and his first co-host, Peggy Knapp. Via WHYY.

First on, around 6:30, was back-to-back episodes of Hometime, with Dean Johnson and a revolving cast of female co-hosts. They would explain some sort of construction task in prosaic, Mid-western inflected dialogue, carrying on a charade that they were married and living in the house they were working on. It was very confusing to a seven year-old to see Dean with one woman after another (re-runs being all shuffled up), constantly moving to new houses in bad repair. I was often left wondering about his life choices while simultaneously being amazed at his home-improvement chops.

Bob Vila in the prime of his days, via doityourself.com

Next on was This Old House. This tilted towards a slightly older demographic, although, to be fair, I was out of my depth from the second I switched on the TV. TOH episodes were more tilted towards long-term projects, revisiting the same house week after week, checking in on progress. I liked this strategy -- I'm still a sucker for a narrative -- but again, PBS would always shit the bed on re-run continuity. I would wait all week to see how the refurbished butcher-block island turned out, only to see some boring tutorial on birds-mouthing rafters.

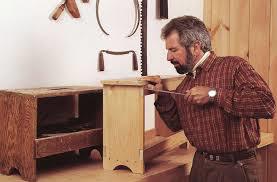

Old-school Norm Abrams (on right), via Flickr member eiandy.

Next, at about 8, was The New Yankee Workshop, with Norm Abrams. By this point, some of my siblings were stirring, but if I kept the door to the back room closed and the volume low, they usually didn't even notice I was in there. Norm was also a host on This Old House, which I also remember being very confusing -- a man on TV is so desperate for cash he needs two jobs? The NYW was about DIY furniture, usually old Arts-and-Crafts-type designs with a lot of straight cuts and simple joinery. However, Norm had an insane shop, with every tool imaginable, and, in even in my childhood, I realized that it was unrealistic to have much beyond a table saw. Looking at our own family garage, I quickly realized even a table saw was probably a ridiculous dream.

Roy Underhill, the godfather of DIY TV crazy.

The last show of the morning was always the best. The Woodwright's Shop, hosted by Roy Underhill, used only hand tools, most of them ancient. He brought a manic, unscripted energy that the other shows didn't have, with their painstaking dialogue and scripted situations. Roy was just up there, planing or chiseling like a maniac, a little bit of spit flying when he talked. His projects were usually kind of impractical, but also appealing to a kid -- lacking power tools, it seemed within my grasp to be able to cut, carve, or whittle something out of a branch in the basement.

Jimmy DiResta, YouTube guerilla, via worthpoint.com.

DIY TV has proliferated, although not always in a good way. HGTV and The DIY Network shops are generally worthless, filled with flawless hosts performing improbable feats in impossible timelines, never mussing up their mascara.

Others are out there swinging, hacking away like true guerillas. Jimmy DiResta churns out crazy from his basement lair in Manhattan, making freehand table saw cuts and building guitars that look like AKs. His video style is sped-up time lapse, replete with the sped-up noise instead of music. The results are raw, a little unpolished, but clearly informative and lacking in any bullshit production values.

Chris Hackett had a short-lived show on the Science Channel that lives on in the bowels of the internet. Co-founder of an art collective, The Madagascar Institute, he thrives on trash -- obtanium, he calls it -- bending it into metal foundries, unlikely vehicles, and fire-breathing apparatuses of all kinds. He is an instructor for the apocalypse, what might be termed post-Rapture DIY.

I've messed around with a few time-lapses, and hope to make more. Maybe some seven-year old will watch them on his parent's iPad in the back room on a cold November Saturday, before his parents wake up and make him eat his Wheaties . . .