Blog

Search the O.G. Archives

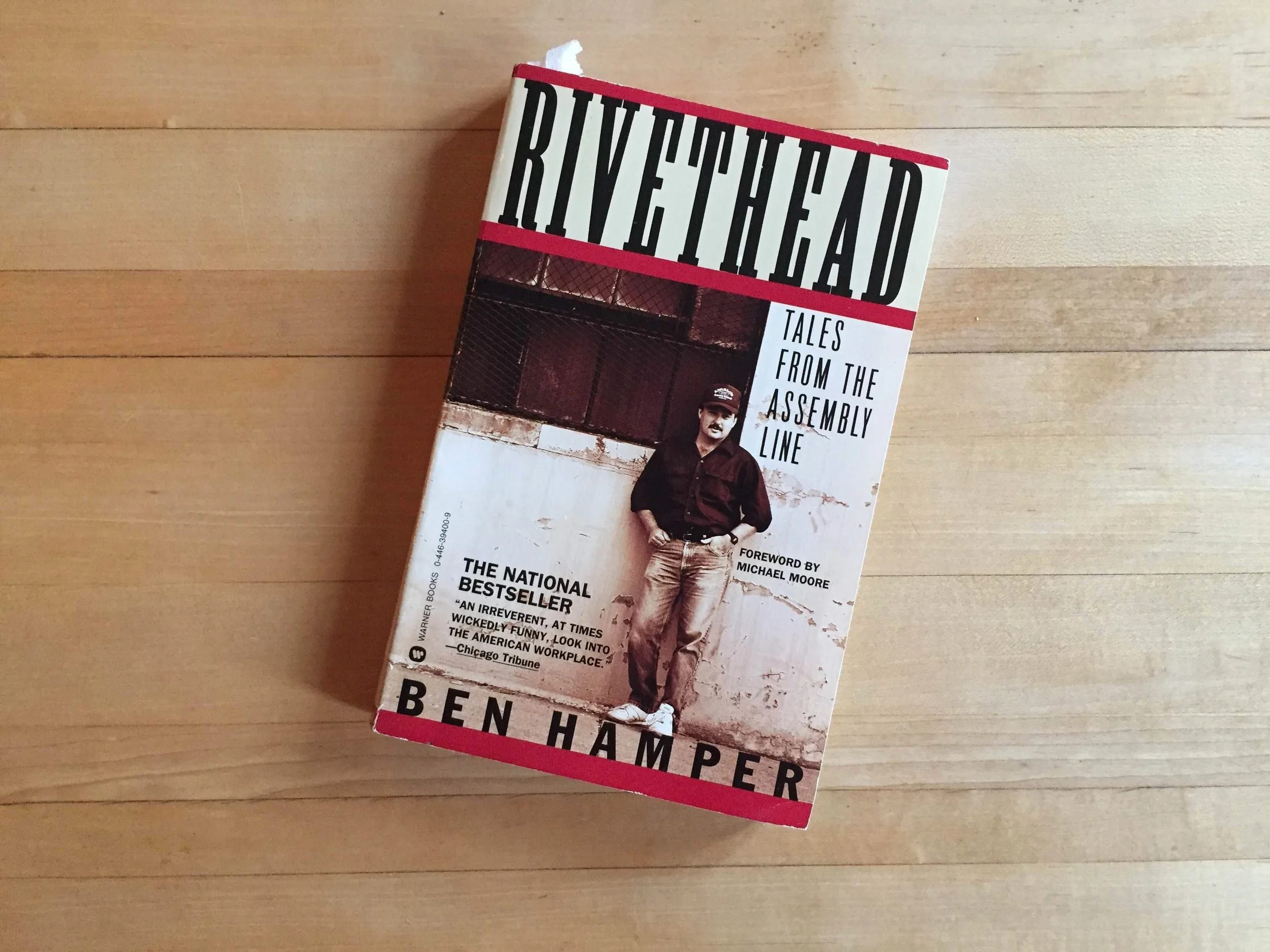

I stumbled across Rivethead: Tales From the Assembly Line, in an off-hand comment in our cranky local alt-weekly, The City Paper. God bless 'em, alt-weeklies still exist, a healthy weekly dose of casual profanity, pinko editorials, normcore cartoons, and weepy art criticism, held together with mis-registered newsprint and strip-club ads. I ordered it used and read it in just a few days.

Ben Hamper was born in Flint, Michigan, in 1956. He was a 4th generation assembly-line worker -- his great-grandfather joined the workforce in 1916, only 15 years after the assembly line was invented. He grew up standard mid-century Catholic: a half-a-dozen siblings, a drunk dad who was in-and-out of work, and a regimen of parochial schools. He ended up married with a kid on the way after barely graduating high school.

A few years later the marriage went south and Hamper went looking for serious work. Partly it was a ploy to repair his relationship, but it also seemed ancestral, like the dull pull of the mills had been ground into his blood. The late seventies weren't great years for the domestic auto industry -- the beginning of a rough two decades -- but he eventually found work at the General Motors Bus and Truck Plant on the night shift.

On New Year's, a book fell into my lap via some friends that felt like a good omen going into promising year: The Dome Builder's Handbook, by John Prenis. It sits right in a narrow vein of 60s and 70s-era design writing that I've written about here many times before, dense with hand-drawn illustrations, DIY promises, and anti-establishment ethos. It may, in fact, be a peak example of the type, second only to the Whole Earth Catalog in its complete adherence to the conventions of the form.

I haven't been able to find much information about John Prenis or the circumstances of its publication, which only adds to the mystery. This was Prenis' first book; he wrote seven more, with the last coming out in 1990. The Dome Builder's Handbook came out in 1973 as one of the first titles for Running Press. The publishing house still exists, with the name surviving a 2002 merger with Perseus. All of Prenis' subsequent books were also published by RP, but their current catalog doesn't list any of his work. In general, their selection seems to have pivoted away from craft and DIY titles and into children's and cookbooks.

I have been looking into zip ties for furniture construction for a few years now. The Zip Tie Lounge Chair went up for download a year and a half ago. I was pretty pleased with it at the time -- I had tested an unproven notion and it worked! -- but it's really just a first iteration. It has worked out ok, but it hasn't fully solved the design problems. There are a couple of outstanding issues:

+ Over time, it has become apparent that zip ties aren't great for rigidly connecting plates at right angles. A zip tie naturally forms into a slightly-teardropped loop as you pull it tight, so they never fully draw when wrapped around a right-angled butt joint. Then the plates flex every time someone sits in it, and the friction gradually loosens the chair and makes the ties to snap.

Back in early October, I had a chance to get up to the Hudson Valley, an hour past New York City. Fall was just beginning (and seems to never end this year), with trees turning under the pressure of cold nights and crisp mornings. We stayed in a hard-luck town called Newburgh, across the Hudson River from Beacon. While both sides have rail lines, Beacon has the commuter train to New York City, and so has become an uber-outer suburb, full of Brooklyn expats, nice coffee spots, and farm-to-table restaurants.

Years ago, in my first trip out west, I went to Donald Judd's sprawling Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas. We revisited it a few years later in between Chicago and Baltimore. Now, it was time to meet its east-coast twin, Dia:Beacon.

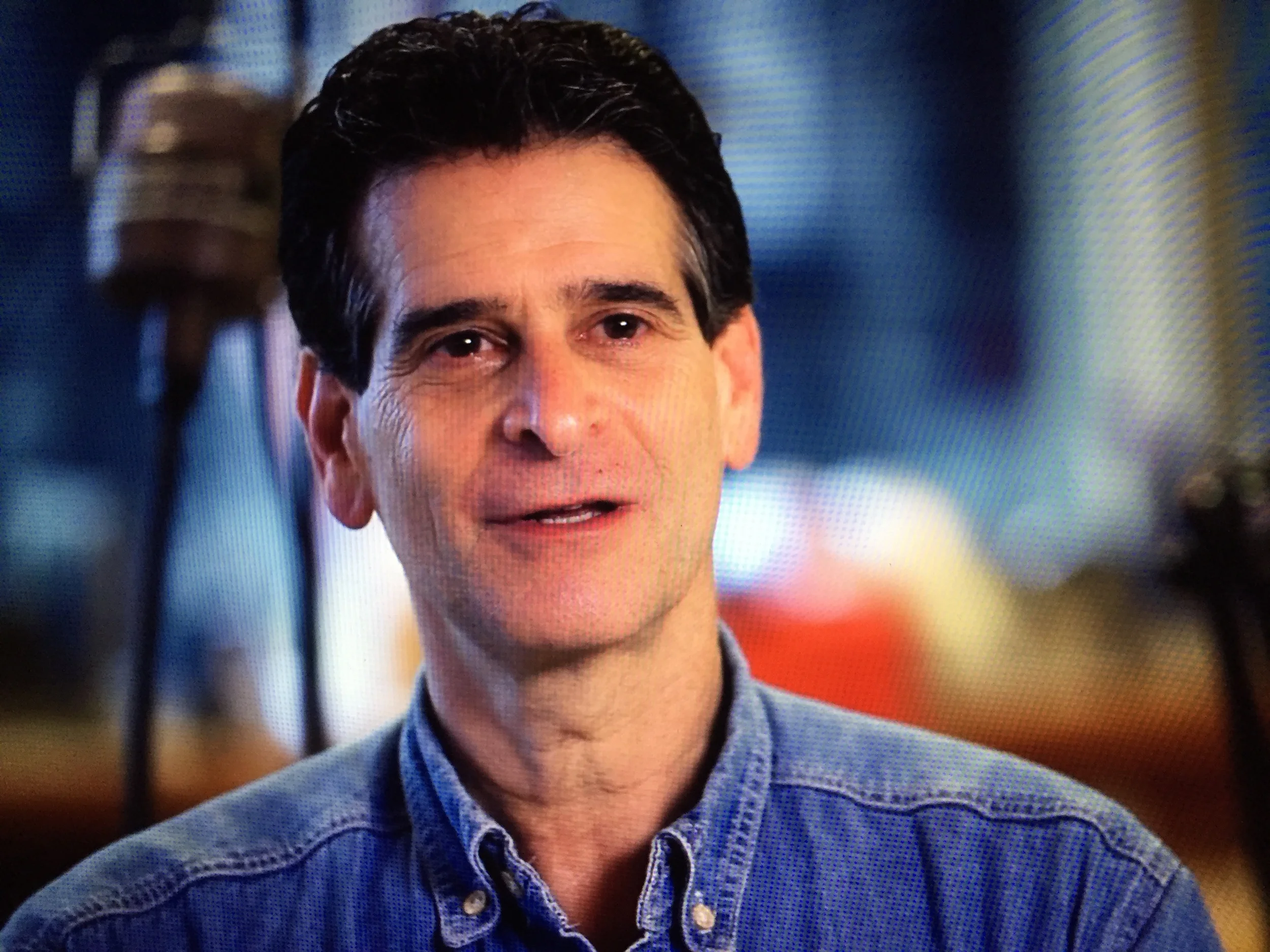

The other night, I watched SlingShot, a documentary about Segway inventor Dean Kamen. Despite some withering reviews (this one from the LA TImes is pretty spot-on), I was curious about Kamen ever since reading a profile of him a couple of years ago. Now a self-made millionaire, he has invented dozens of medical devices, a self-balancing wheelchair, and is now working on the SlingShot, an off-grid water-purification plant.

The film, hagiographic and stiff, paints Kamen as a lone, eccentric genius in the mold of Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, or Nikola Tesla. He is a lifelong bachelor (confirmed by an interview with his sweet, elderly parents), too married to his work to have time for a family. He pilots a helicopter from his house to his downtown research lab. He wears identical clothes everyday -- Jay Leno-esque head-to-toes denim. The list of genius tropes goes on, building Kamen up to the task of taking on the world's biggest problem: clean water.

The other week, I was walking to the grocery store -- a little over a mile, by alley as much as possible. Alley-walking is one of my favored pastimes. I can forage for building material, avoid cars, and get a little exercise.

I came across this house, 3815 Crowther Street, tucked at the end of a dusty gravel no-mans land between Hickory to the east and Falls to the west, hemmed in on all sides by alleys (though I guess one of them is technically a street.) It faces nothing, with an abrupt front only made discernible by the slope of the roof. For the last two years I've been living in this neighborhood, I passed the house dozens of times -- windowless, unpointed brick standing like a little kid's bad dream.. It struck me as a great fixer upper -- I'll get in cheap, strip it down clean, whitewash everything, studio downstairs, living space above -- but the location was unusual.

Last week, I had the opportunity to share some of my trials and tribulations as a worker in the user innovation economy at a seminar at the MIT Sloan School of Management. I was invited by Eric Von Hippel, an economist who has been at the forefront of studying "specializing in the nature and economics of distributed and open innovation." While we now take open source software for granted as a permanent feature of the Internet, let us remember it wasn't always thus, hampered by restrictive licenses, high cost, and general user unfriendliness. And, professor Von Hippel practices what he preaches, releasing his papers and books free online for unrestricted download.

My presentation concerned my experience in the user-driven economy, through the lens of four experiences: selling items on Etsy, posting projects on Instructables, writing Guerilla Furniture Design for Storey Publishing, and putting out designs on Open Desk. My basic thesis was that while online platforms have lowered the barriers to entry around design-based businesses, they haven't lowered the barriers to success at all.

Last year, I got a chance to the World Maker Faire for the first time. The experience was mixed; it was beautiful weather, with huge crowds, but presented in a chaotic way. I took some issue with other aspects of the enterprise (maybe a tad harsh here) which seemed at odds with some of the maker movement's stated principles.

This year, I had a different experience with Maker Faire. I returned as an exhibitor -- to give a talk about Guerilla Furniture Design at one of the live stage tents. I also have learned a lot more about the maker economy and related fields in the intervening year, and have gained an appreciation for how epic it is to pull of an event like that. Along the way, I got to meet some makers and check out a lot of booths. Check out my favorites below.

Karl Hess was a complicated man. Raised by a single mother in 30's-era Washington, D.C., he dropped out of high school and got into the news business at age 15. By his early forties he was writing speeches for Barry Goldwater; he then swung to the other end of the spectrum, joining Students for Democratic Society (SDS) and collaborating with the Black Panther Party. Eventually, he struck out for unknown territory, espousing a radical form of libertarianism that bordered on anarchism. He wrote a number of books, including Community Technology, which first came out in 1979 .

I first learned about Hess in an article that used a term, shared machine shops, attributed to him. I got a used copy of Community Technology put out by Loompanics Unlimited, a reprint house covering topics like drugs, smuggling, anarchism, and survivalism. These titles proved controversial enough to attract the attention of the F.B.I., and they went out of business in 2006. These sit slightly to the outskirts of the sort of seventies-era DIY manuals that I have soft spot for -- Shelter, Hydroponics Hot House, The Passive Solar Dome Greenhouse, The Prodigious Builders, Nomadic Furniture, and How to Build Your Own Living Structures. They are all lightly political, explicitly practical, and more than a little self-righteous.

Towards the end of March, I went to Iceland for a week with the lady. Neither of us had been abroad in years -- it had been a decade for me -- and there are pretty cheap direct flights from Baltimore, so we took a chilly spring break excursion to Europe's wildest island. We took an overnight flight, landing at 6 AM, then rented a little hatchback and headed into Reykjavik. After breakfast, we napped in the car and then checked into our AirBnB. Later, we poked around the capital's design district, which boasted an impressive array of Made in Iceland products.

We used AirBnBs every night except one -- the hotel system in Iceland seems to be mostly guesthouses and hostels, and the AirBnB listings were transparent (and cheap!). Reykjavik was a startlingly clean, modern, walkable city, built in a kind of vernacular modern style that was hard to place. It was part Bauhaus, part Scandinavian, and part Rural Studio, all galvanized tin siding and steep roofs.