Community Technology

Karl Hess was a complicated man. Raised by a single mother in 30's-era Washington, D.C., he dropped out of high school and got into the news business at age 15. By his early forties he was writing speeches for Barry Goldwater; he then swung to the other end of the spectrum, joining Students for Democratic Society (SDS) and collaborating with the Black Panther Party. Eventually, he struck out for unknown territory, espousing a radical form of libertarianism that bordered on anarchism. He wrote a number of books, including Community Technology, which first came out in 1979 .

I first learned about Hess in an article that used a term, shared machine shops, attributed to him. I got a used copy of Community Technology put out by Loompanics Unlimited, a reprint house covering topics like drugs, smuggling, anarchism, and survivalism. These titles proved controversial enough to attract the attention of the F.B.I., and they went out of business in 2006. These sit slightly to the outskirts of the sort of seventies-era DIY manuals that I have soft spot for -- Shelter, Foxfire, The Passive Solar Dome Greenhouse, The Prodigious Builders, Nomadic Furniture, and How to Build Your Own Living Structures. They are all lightly political, explicitly practical, and more than a little self-righteous.

Love the cartoon cut-away diagram covers!

Community Technology is based on three years that Hess and his wife, Therese, spent living in Adams-Morgan neighborhood in D.C. in the late seventies. Now filled in with condos and bars, it was then an impoverished, predominately African-American neighborhood. Hess and his neighbors formed a community group, the Adams Morgan Organization (AMO). After a few succesful community clean ups, Hess fell in with a smaller group that began undertaking experiments in radical self-governance and community technology. They raised fish in basement tanks, grew food on rooftops in greenhouses, hacked together windmills from auto parts, and installed solar hot water heaters. All of these homegrown hacks were documented in a library. Hess threw himself into the work, and Therese worked to support them.

What Hess doesn't say in the book was that he couldn't work in a legitimate economy. As a political protest, he refused to pay taxes, and had his wages garnished by a prosecutor at a rate of 100%. In counter-protest, he dropped wholly out of the legitimate economy and operated only on barter. In the first chapter, he alludes to these troubles at then end of an eloquent rant against rampant consumerism.

"Because this book is about technology which has very personal dimensions, it requires a personal statement. Unfortunately, it is likely to sound outrageous. If it does, please understand that it derives from experience and not from ideological frenzy.

I have worked very hard and very long under the impression that success is money, that time is money, that progress is money, that money is wealth.

I am convinced now that there are other possibilities. " (pp.5-6)

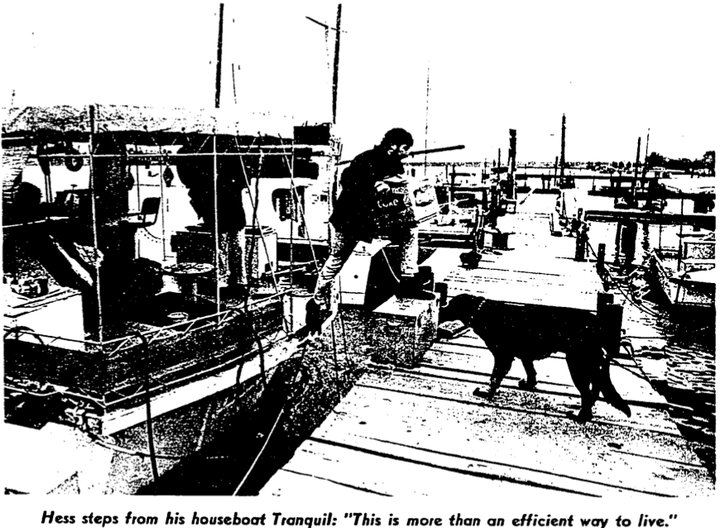

Hess; apologies for the graininess but not a lot of pictures out there of him.

Hess goes on to make a lot of questionable assertions, drawing from a number of fringe elements in American politics on the left and the right. But, the second half of the book, dealing with his theories of community-based economies, sound remarkably similar to some of the noises coming out of the maker movement. Hess advocated that every neighborhood establish shared machine shops and materials warehouses to establish grassroots-up cottage economy. Instead of complex assembly lines churning out millions of selfsame widgets, flexible, distributed micro-factories could provide full employment and material comfort. That sounds a lot like some of the rhetoric about today's Fab Labs.

"In point of material fact, manufacturing has undergone the sort of technological change that has characterized all science-based activities in this century -- a distinct tendency toward decentralization and small-scale units. A truly modern cybernated plant, turning out o a vast array of machine parts, for instance, can be housed easily in a city neighborhood, in office space. It uses computers to direct its tools, and can be handily operated by workers in the neighborhood." (pp. 32-33)

The prediction is almost eerie -- with CNC and laser-cutting technologies decades away from commercialization, the Internet just a military project, Hess seemed to anticipate the rise of everything from OpenDesk to Kickstarter. He discusses about shared databases of blueprints, available to anyone to make stuff in a shared machine shop -- Wikipedia, YouTube, Instructables. He even makes a case for a distributed electricity grid and neighborhood-based copower -- SolarCity, Vivint, Powerwall, neighborhood batteries.

Hess in New York, circa 1970. From the Karl Hess Institute Facebook page.

However, for all his revolutionary zeal, Hess doesn't include a single diagram in the book. The other books I mentioned above all come with detailed plans, photographs, charts, and step-by-step tutorials alongside their philosophical opinions. Without them, Community Technology feels a bit vaporous, kind of like an oral history of a mythological place where people made their own food and energy without any real sense of how they did it.

Tired of infighting and plagued by robberies in Adams-Morgan, Hess and his wife lit out for West Virginia around 1980. He starred in a short documentary, Toward Liberty, that won an Oscar a year later. He and Therese built a self-sufficient passive solar house in the woods, publishing sporadically and experimenting further with appropriate technology systems. Hess ran an enigmatic campaign for governor as a Libertarian in 1992, and passed away two years later.

Hess's legacy can be seen a number of modern projects, some born directly from his experiments seventy years ago and some evolving from the fringe. The Institute of Local Self-Reliance came out of D.C. in the seventies as a peer to Hess' work; it lives on now as a libertarian think tank. Open Source Ecology is using modern technology to fulfill some Hess' original aims, including self-replicating machines and distributed manufacturing. The concept of appropriate technology has gained currency in the wake of troubled projects like One Laptop Per Child.

Though his politics were at times questionable, Hess was the type of radical society needs from time to time. He was often irrational, always stubborn, and wholly convinced the whole system was rigged -- and he offered a framework for solutions. I think today's maker movement may finish his thought.