The term "planned obsolescence" was supposedly coined by Milwaukee-based industrial designer Brooks Stevens in 1954 for a presentation in Minneapolis. However, a search onGoogle's Ngram tool, which tracks the prevalence of phrases in books over time, traces the first appearance of the expression to 1929. Stevens couched its use in different terms than it has come to be understood today: “Instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary.” He thought of planned obsolescence not as a set of design flaws time-delayed into the infrastructure of a product, but more of a marketing ploy meant to make the old versions look out-of-date. Car companies, with their yearly model changeovers, are masters at this; phone companies have aped their success at a cheaper price point.

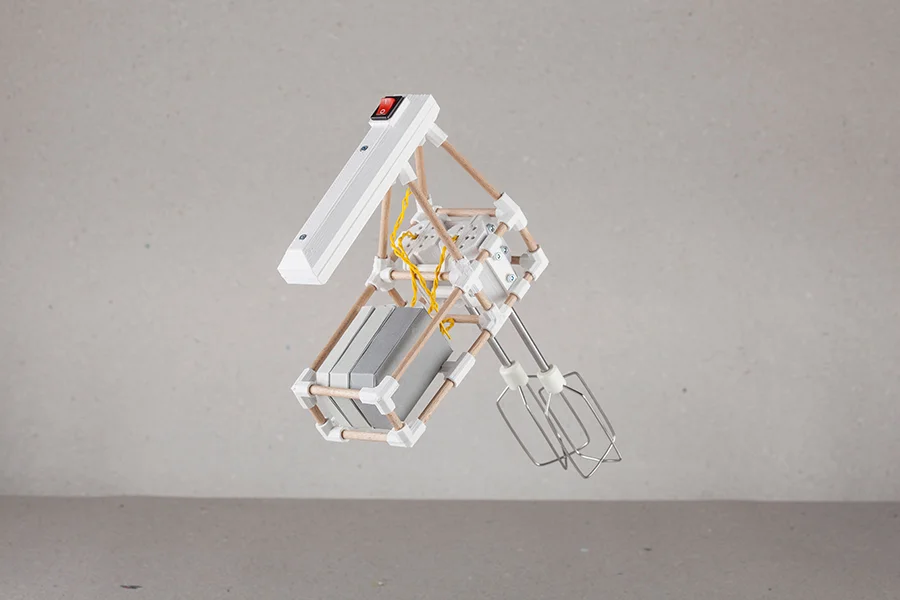

In the era of software, executing planned obsolescence has become easier than ever. An operating system update pushed out to devices with little or no choice from users can savage functionality. The practice of "instilling desire in the buyer a little sooner than necessary" is now a centralized, push-button operation. These software manipulations are inextricably linked into a whole ecosystem of difficult-to-repair hardware built with proprietary fasteners, edge-to-edge screens, and finicky, expensive batteries. Recently, I wrote a post on this sad back-and-forth, as illustrated through designer Thomas Thwaites' attempt to build a toaster from scratch.

Read More