Knolling (Orthogonal Joy)

Last week, America voted. Design Observer published an interesting piece on the arrangement of polling places. The layout of these school cafeterias, church basements, and VFW halls are up to the individual poll workers, and often follow no particular order. That said, people instinctively tend to set up space in certain ways -- for instance, arranging the voting booths parallel to the walls of the room, or figuring out paths for lines of people that make ninety-degree turns. The author, Alexandra Lange, then moved on to riff about "knolling", a term coined twenty-odd years ago by Andrew Kromelow, then working in Frank Gehry's fabrication shop. It refers to the practice of placing objects in squared arrays, aligned with the surface they rest on or the walls of the room that contains them. Kromelow, cleaning up the workshop each night, would neatly lay out all of the tools on the pegboards and work benches. As legend has it, Gehry was then working on a line of furniture for modernist heavyweight Knoll, and so Kromelow named his practice after the angular pieces. Another artist, Tom Sachs, popularized the term and made a video about it, Always Be Knolling.

Now, in the era of Instagram and Tumblr and Pinterest and all the rest, we are besieged with knolling. Just this week, an epic knoll made it into the New York Times magazine, showing a family with all their "prepper" survival supplies. The practice has turned into a show of hipster force, with twee photographs of vintage cameras, facial hair grooming supplies, and old video games. The barrage of images, like a lot of things on the internet, quickly exhausts me. These arrangements hover uncomfortably between information and art, trend and iconoclasm. Unfortunately, they usually veer off into garden-variety dumbassery.

The Douglas family, a-knollin' and a-preppin'. In the original photo, via the New York Times, each circled number relates to a caption (rice, dehydrated mashed potatoes, first aid kit, etc.), including one that says "Douglas family".

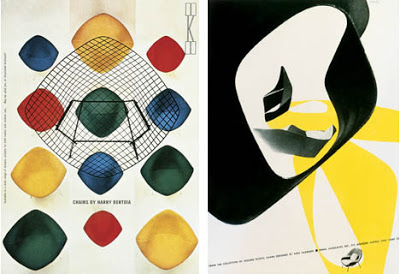

That said, the term knolling also has firm mid-century roots. Vintage Knoll catalogs use a strong visual language of primary colors and orthogonal arrangements of handsome line drawings, fabric swatches, and clean, hard-edged photographs. Their ads and graphic identity from the fifties and sixties was visually stunning and has aged remarkably well. The Eames' were famous for their "knolled" photographs and exploded diagrams for catalogs and advertisements. The New York Times cooking blog, under venerated food writer Mark Bittman, has adapted a precise, clean aesthetic at least partly based on knolling.

From Mark Bittman's "Eat" column in the Times.

Vintage Knoll ad.

Eames!

So what is the appeal? Why does this visual rubric persist? I am engaged in informational writing, often attempting to illustrate processes through photographs and words. In the woodshop, while working on an Instructable, or just documenting a piece I'm building, I've often wished for some version of the NFL SkyCam that would take neat overhead photos of every step. Instead, the views are often perspectively skewed, clouded by dust, and muddied with visual background noise.

One of my attempts, from the Bent Cardboard Chair post.

First of all, knolling makes complex information simple and relatable without diluting the amount of information. The simple act of organization makes things accessible. Second, the strict orthogonal logic allows the eye a logical path through a dense field. Third, anyone can do it! Unlike infographics, or other forms of visual organization that require more complex tools and training, knolling is available to anyone, anytime, anywhere, with anything.

One of the old knocks against modernism is its reliance on the grid, simple angles, and rigid geometry. Many a hippie architect has argued in favor of round buildings, following some sort of the-earth-is-round-nature-is-curvy line of reasoning. But orthogonal logic is relentless. The shortest distance between two points is a straight line. Gravity acts perpendicular to the surface of the earth. Our bodies fold into ninety-degree patterns -- at knees, hips, and elbows. Round shapes are fiendishly difficult to build with any degree of accuracy.

I believe our reliance on the grid is innate, an inborn dependance on reliable, measurable visual information that helps us navigate a confusing world.

And so we knoll.