Shigeru Ban, Pritzker Laureate

About a week ago, Shigeru Ban was announced as the 2014 Pritzker Laureate. Established in 1979 by Jay and Cindy Pritzker, the yearly award honors a living architect for "whose built work demonstrates a combination of those qualities of talent, vision, and commitment, which has produced consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture." The Pritzkers, native Chicagoans, made a fortune at the helm of the Hyatt hotel chain, and modeled the award on the Nobel prizes. Laureates receive a $100,000 cash prize and a bronze medallion.

In the past, the award has mostly honored older (at least in their sixties) architects for producing a solid collection of major buildings, pushing forward the field through form and theory. It's always been a sort of inside-baseball prize, for "architect's architects", those of weighty monographs and leaky roofs. Some, like Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid, were better known for their writings and drawings, and used the validation of the prize to win some major commissions. Grumblers referred to them as "paper architects," more famous for unbuildable, extravagant thought experiments than built work. Ban has turned that sly derogative on its head, rising to acclaim because many of his buildings are literally made from paper.

Probably the best known image of Mr. Ban's work, the Japan Pavilion at Expo 2000 in Hanover, Germany. It is a grid shell composed of lacquered paper tubes.

Ban's elevation into the canon (at 56, one of the younger winners) produced some consternation amongst critics and a backhanded compliment from the paper of record, saying "Mr. Ban also represents a kind of anti-architecture, a rejection of the aura of celebrity status pursued by many in the profession." Some critics took to Twitter, dismissing his work as "good enough" or a "defensive play" by a jury acutely aware of the lack of diversity and social engagement amongst previous winners. The selection committee has always favored producers of enigmatic forms, rewarding sculpture over practicality. The odds-on favorite this year was Steven Holl, whose perpetual short-listing is turning him into the Dan Marino of architects.

Patrik Schumacher, partner at Zaha Hadid Architects, took to Facebook to protest "political correctness" in architecture, writing "as if the delivery of social justice is the architect’s competency" and arguing that an architect's only duty is to be pushing forward form. Schumacher favors an invented style he has named "parametricism", which uses sophisticated 3-D modeling software and algorithms to derive structure. Pioneered by Frank Gehry (Pritzker '89), software has allowed for the ideation and construction of buildings that would've been impossible a mere 30 years ago. To those on the bleeding edge of the field, Ban's work seems reductive, simplistic, and, well, boring.

Got this bad boy the year it came out, upon my graduation from architecture school.

In their rush to prove that Ban only won the Pritzker for his work on headline-grabbing humanitarian projects, and not any particular understanding of theory, critics seem to breeze by his long-term iterative material research, rigorous interrogation of traditional Japanese forms, and his acute sensitivity to cultural and vernacular pressures. Matilda McQuaid's excellent 2007 monograph on Ban, one of the first comprehensive surveys of his work, is divided into sections by material.

She starts by examining paper, Ban's most well-known canvas, then explores bamboo, wood, and prefabrication. Each section includes engineering tables and data, especially on the strength of the paper tube structures. Over the years, Ban has experimented with wood, aluminum, steel, tape, rope, and even zip-tie joinery in his paper and bamboo structures, lab-testing each for failure thresholds. Lavishing such attention on the joint, one of the fundamental units of architecture, is a nod to the Japanese tradition of design. It is also a prime example of research through making, an approach to design that is being increasingly lost inside the computer. Within the screen, one can iterate endlessly without learning anything.

Many of Ban's critics and opposites-- Schumacher, Hadid, Gehry, Herzog and de Meuron -- have tried hard to banish the joint, turning all of architecture into pure surface. This approach ignores fundamental construction realities, requiring expensive, complex, and wholly hidden forests of irrational columns and trusses. The resultant structures are thin, all facade -- the definition of "paper architecture."

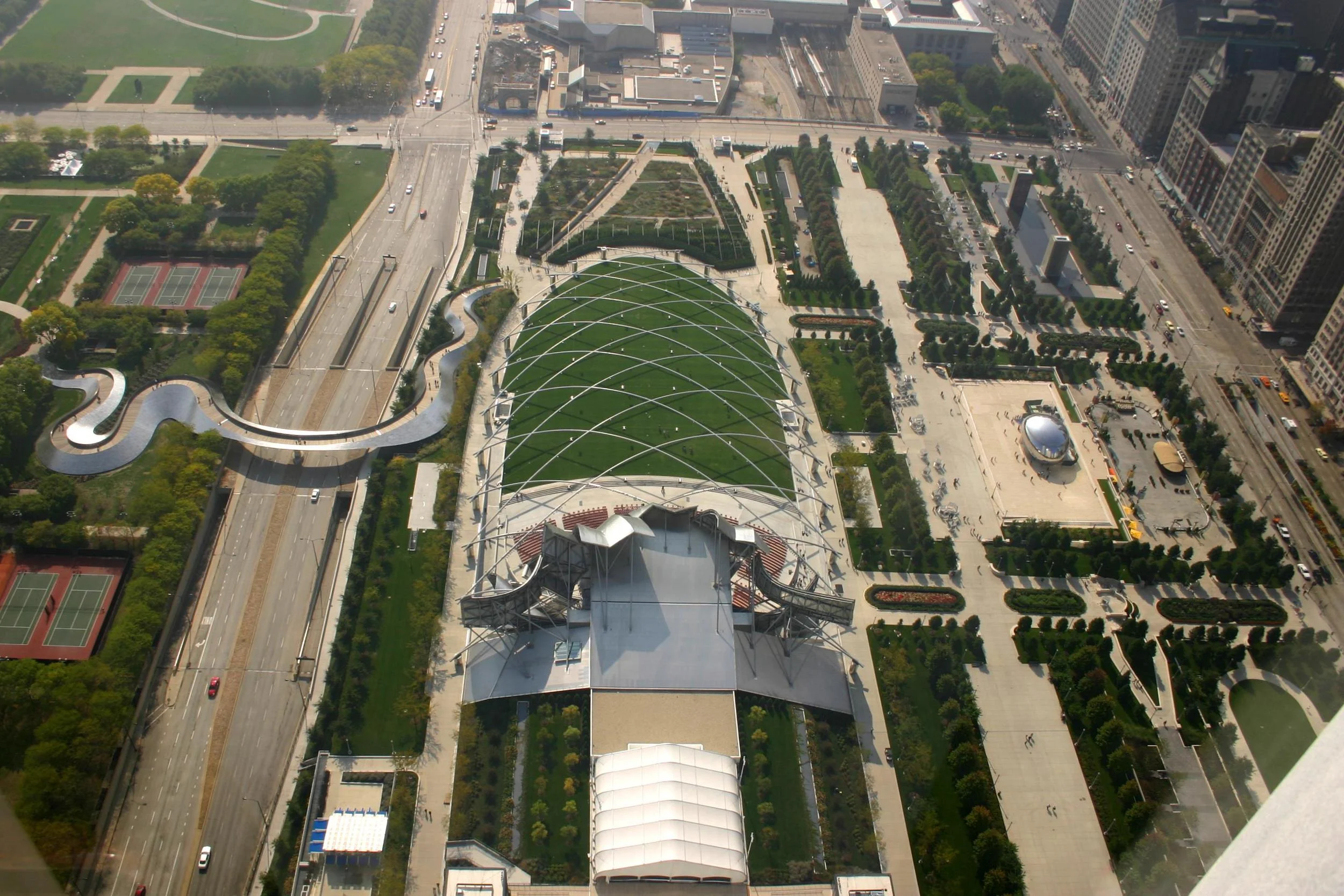

The Jay Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park, in Chicago, is a prime example of Gehry's one-dimensionality; almost never photographed from this angle, his famous amphitheater is a billow of sheet metal propped up by an ugly tangle of carefully concealed structure.

In one way, Ban's projects are classic modernism -- they radically open the floor plates, clearly express structure, separate shell from skin, use industrial materials to domestic ends, and turn the building's bones into ornament. In another way, they are subtly subversive, finding organic forms within rigid geometry and adapting themselves to place. Ban touches the landscape as lightly as possible, radically de-materializing to the point of improbability. Some of his refugee shelters use rubble-filled beer crates as foundation. One house uses plastic bags filled with packing peanuts for insulation. Nearly every building he's made consists of de-mountable joints and articulated pieces, easy to disassemble with nothing but a ratchet and some time. His refugee shelters for India, Turkey, Japan, and New Zealand all make concessions to local culture, re-shaping themselves to provide unconscious measures of comfort for people entrapped in difficult times.

No wonder people are pissed! He stands like a whisper against all the chest-thumping dogmatics out there imposing forms on the world, putting up absurd towers in Dubai or spaceships in Silicon Valley. Everything he does questions permanence in architecture, pushing back against the egoism of edifice and reminding architects that their prime directive is to provide shelter, however humble it may be. He returns architecture to its rightful place in service of the Vitruvian triad -- strength, beauty, utility -- disarming the shouters that seem to have abandoned all three, chasing mirages in the desert.

Who knew so many giants could be slain with a cardboard tube?

Ban in his own words, TEDxTokyo, 2013.