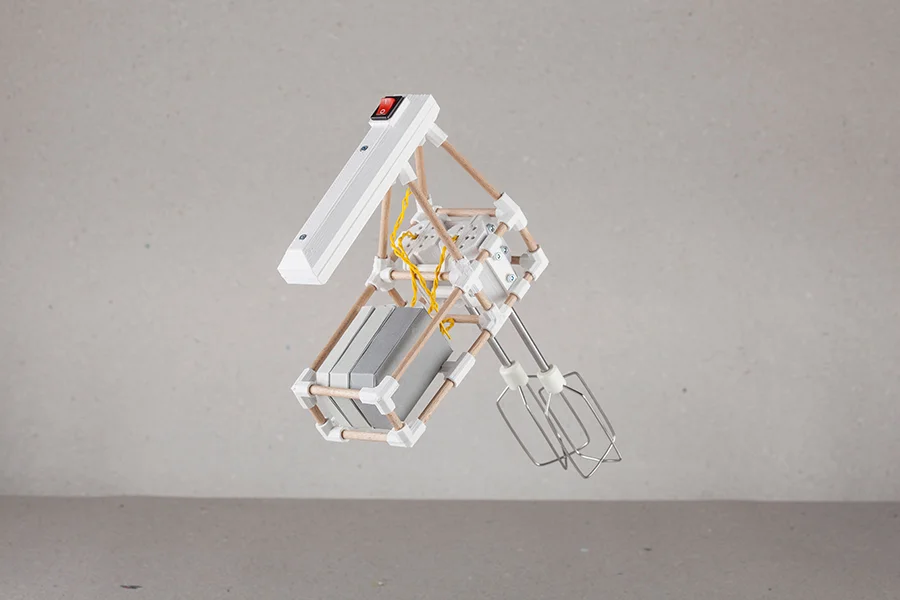

Just over a year ago, I was invited to exhibit and speak at Z0: Digital Fabrication and the New Language of Materiality at Gallery 788 in my home borough of Hampden here in Baltimore. The show was being organized by Fab Lab Baltimore, an open-access digital fabrication facility at Community College of Baltimore County-Catonsville. I had been visiting there over the preceding few months to prototype the Zip Tie Lounge Chair, which I exhibited as a whole object and with the exploded parts hung on the neighboring wall. The staff had been radically patient with me, through broken bits and dumb questions, and I was flattered to be asked to show my work.

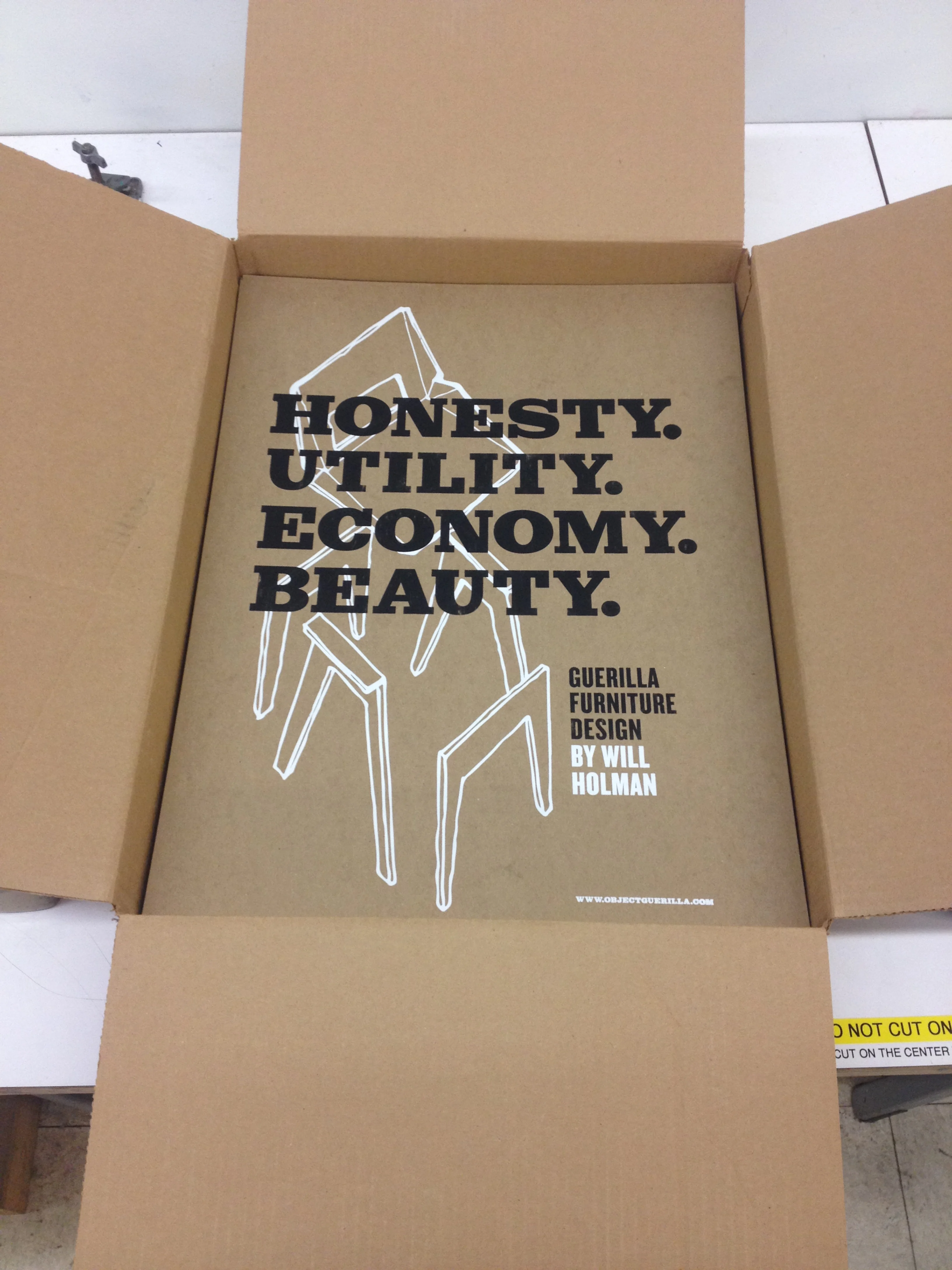

I was a little nervous -- still getting my public-speaking legs under me -- but I said yes, and spoke a bit about my history as a furniture designer, my (then-upcoming) book, and how was I was moving towards exploring digital fabrication. Afterwards, a Boh or three deep, I fell into conversation with Tom Burkett, of Baltimore Underground Science Space, and Jason Hardebeck, of the Baltimore Foundery. That conversation planted the first seeds for what would become the Industrial Arts Collective.

Read More